When one thinks of the likes of medieval Scotland, many images are stirred up; misty glens, an untamed wilderness, warring clans, attempts of conquest by the English, and, of course, castles!

There are a great many castles around Scotland, many in secluded areas, built by nobles and clan chiefs as a means to defend their land. But two castles will always spring to the mind; Stirling and Edinburgh. Both cities’ castles are steeped in history; these royal strongholds have seen sieges and occupations across their many wars, they’ve both been expanded by their regal occupiers over the centuries, and they both lie at the heart of their respective cities.

One may well ask, then, “where is Glasgow’s castle?” A good question indeed, especially for a city of such importance to the Church in Scotland. Go a little outside of Old Glasgow and you’ll find one or two castles worth visiting; Bothwell, Crookston, Cadzow (though you cannot currently visit this site), or even Dumbarton if you fancy going a little further out. So what of in the city itself?

Well, there is a street in Glasgow called “Castle Street” which provides our first clue. This street runs from the top of High Street at Rottenrow along to where is becomes Alexandra Parade around the Royal Infirmary. Yet, other than the Provand’s Lordship and the Cathedral, there’s nothing very medieval looking – let alone Castle-shaped – in the vicinity. But there once was.

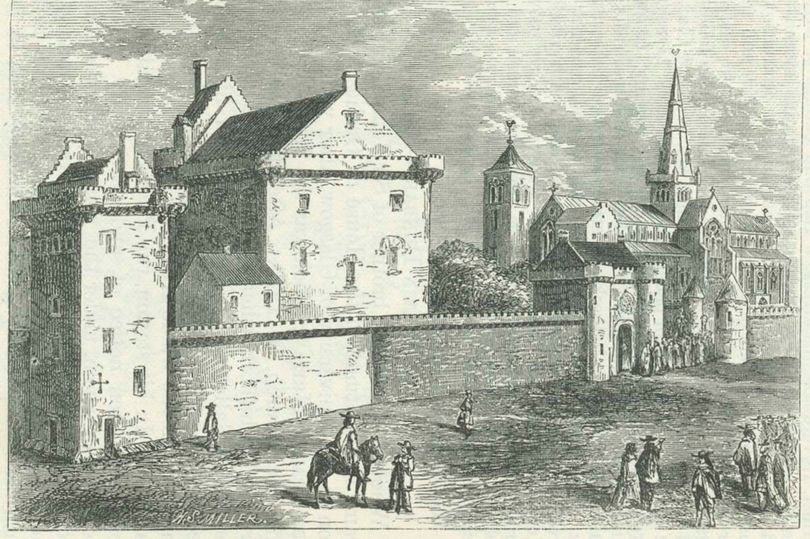

Image from the Mitchell Library

The castle started out small, but at its height was an imposing structure. Its two-towered gatehouse, square tower on the southwestern corner, its high walls, and its grand, five-storey keep made for an impressive show of power. The bishops and archbishops of Glasgow had a great deal of authority, and they knew how to make a show of it.

The Castle’s origins aren’t wholly clear, but details of a royal stronghold on the site go back as far as the twelfth century. By the fourteenth century, it was under the control of the church, and, through the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, saw a great degree of enlargement.

By the mid-sixteenth century, however, it was already in ruins. The last catholic archbishop of Glasgow, James Beaton, fled to France around 1560, with the Scottish reformation in full swing. Archbishop John Spottiswoode of St. Andrews/Glasgow post-reformation – himself a University of Glasgow Graduate – ordered the restoration of the Castle in the early seventeenth century. In the 1680s, Archbishop Ross attempted another restoration. But by the eighteenth century, the Castle was largely in ruins once more.

With the Scottish Reformation having taken power away from the Catholic Bishops in Scotland, and the move towards a Presbyterian system of governance for the new Kirk, there were no longer bishops to occupy and maintain the castle. The early eighteenth century saw some of the more intact parts of the castle used as a prison, but as that century progressed, more and more of the old castle disappeared.

Image from: http://www.rareoldprints.com/z/19772

Stone and other materials were taken – both lawfully and not-so lawfully – from the site for the building of other structures. By the late 1700s, the castle was very much in a ruinous state. The final blow for it came in the 1780s, when the Town Council declared that the castle was to be demolished and the Royal Infirmary (not the one we know today, mind) built on its site.

Today, the site looks quite different. The approach to the Cathedral is now wide open at the top of Cathedral Street – this wide, tree-lined precinct now gives a view to the front of the Kirk from along the street leading up to it. The castle’s keep, though long-gone, is still marked by a small monument on the precinct itself.

That all being said, the despite the fact that the Castle is long-gone, the square in front of the Cathedral doesn’t simply sit empty.

In 1993, the Saint Mungo Museum of Religious Life and Art opened on the site of the original castle – close-by to where the keep would have stood. The museum was constructed in a style similar to that of the old Bishop’s Palace and is now a landmark in its own right. The Scottish Baronial style, the southern turret, the stonework, and many other well thought-out features all evoke a medieval feeling in a building that is, quite decidedly, modern.

The museum, whilst a modern structure and, perhaps, not quite as imposing as the old Castle, is an example of Glasgow recognising its heritage and remedying its past mistakes and neglect. It now, along with the Cathedral and the nearby Provand’s Lordship, forms part of cluster of invaluable resources offering insight into Glasgow’s religious and civic past.

Indeed, with artefacts and information pertaining to countless world religions, the museum is a true symbol of the diversity seen in modern Glasgow. Just as the Bishop’s Palace signified the grip of the Catholic Church on the people of Glasgow, that modern museum in an old style signifies a modern and vibrant Glasgow.

Whilst that complex of buildings erected by powerful clergymen may no longer be there, it’s nice to see that Glasgow has done its bit to ensure their legacy lives on in some way. It’s all too often the case, especially here, that we see building and their stories disappear – at least this time is different.